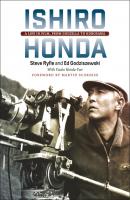

Ishiro Honda. Steve Ryfle

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Ishiro Honda - Steve Ryfle страница 9

Название: Ishiro Honda

Автор: Steve Ryfle

Издательство: Ingram

Жанр: Кинематограф, театр

isbn: 9780819577412

isbn:

Sons followed in their fathers’ footsteps, but such customs began fading in the new era. Honda’s three brothers received religious tutoring at age sixteen, but Honda never did. “None of us really wanted to take after my father and be a monk,” he would recall. “So we started learning about science instead.” Hokan did not try to persuade the boys to live monastic lives, instead urging each one to follow his own path. Though hardly well off, the Hondas made sure their sons were educated. Even with the new reforms, compulsory elementary school was just six years; after that, children from poorer backgrounds often worked to help support their families while students of higher economic or social status continued to middle school (roughly equivalent to present-day high school, spanning ages thirteen to eighteen), and then finally to high school, vocational school, college, or military academy. The Hondas were able to send their son Takamoto to medical school and pay half his tuition; the boy worked to pay the rest and became a military doctor afterward.

Asahi was an agricultural village of about thirty families, mostly rice farmers and silk makers. The roads to the nearest town were narrow and treacherous. There was no library or bookstore, and newspapers were rarely available. Takamoto, a product of the new Meiji ideals, encouraged his little brother to study and regularly sent him books and magazines such as Japanese Boy, Boys’ Club, Kids’ Science, and Science Visual News. Thus, Honda developed a lifelong love of reading and a curiosity about things scientific, despite being all but cut off from the quickly modernizing outside world.

Childhood was a time of simple pleasures. With two middle-aged parents—Honda’s mother gave birth to him at forty-two—there was little supervision, and Honda played from dawn until dusk. When it was hot, he and his friends would swim in the river or build a dam; when snow fell, they went sledding. Sometimes they played hide-and-seek in the temple, ducking behind the mummy’s tomb. There was folk music and dance at village festivals throughout the year, and the Honda brothers all performed with a local youth troupe. Honda was not mischievous, though he once hiked to his cousin’s house across the mountain without telling his parents. When he returned days later, his mother was upset—not that he had gone without permission, but that he wasn’t dressed properly for the visit.

With his stable and happy home life, Honda didn’t develop a strong competitive streak. “I never thought that I had to beat someone else, only that I had to do my personal best,” he recalled. “I never gave thought to being on top … if someone else did better, I would still think and work at my own pace. I was very stubborn in that regard. [But] once I decided to do something, I just had to do it.”3

2

TOKYO

The city of Edo was already one of the largest in the world when, in 1868, Emperor Meiji took power and the capital’s name was officially changed to Tokyo. Its modernization continued as Western influence increased; and by the early 1900s, the rapid expansion of railroads to the plains beyond the city center gave rise to suburbs, with residential neighborhoods “scattered in the fields and wooded hills around long-established farming villages,” according to historian Jordan Sand. These developments became home to people from central Tokyo and, in large numbers, from other parts of Japan.

In 1921 the Hondas uprooted from their tiny village and transplanted themselves to this burgeoning metropolis. Hokan was appointed chief priest at a Buddhist temple in Tokyo, and the family settled in the Takaido neighborhood of the city’s Suginami Ward, a fast-growing suburb on the western side. In 1919 Suginami’s population was roughly 17,000; by 1926 it would soar to 143,000 as families of modest means moved into newly built homes, displacing the area’s rural peasant population.1

Honda was in third grade when his life abruptly shifted from the bucolic mountains to the bustling city; he’d never even seen a train before boarding one for Tokyo. Still, he adapted quickly to his new surroundings. When his classmates at Takaido Elementary teased him about his mountain dialect, he took it in stride and learned to speak like a Tokyoite. He’d been an honors student back home; but the city schools were more difficult, and he faltered briefly before his grades rebounded. His favorite subjects were Japanese, history, and geography; and he continued to cultivate a love of the natural sciences, saving his allowance to buy more science magazines. (Later, in middle school, he would struggle with chemistry, biology, algebra, and other subjects involving equations, but he still liked the scientific mindset.) Despite a drastic change of scenery, many things in his life—family, school, play—were basically the same.

Then he experienced something entirely different. Before Tokyo, Honda had never heard of eiga (movies), but one day at school the students were assembled to watch one. Though Honda would forget the title, it was likely one of the Universal Bluebird photoplays, a series of mostly Westerns that were considered minor pictures in the United States, but were extremely popular in Japan from 1916 to 1919.2 Honda described the film this way: “It was the story of a girl who was kidnapped and raised by Indians. She grew up and found out that she wasn’t one of them. There was a dispute over her, who[m] she should live with … she got on the back of the horse and went off fighting … against her real brother, something like that. I saw it at the schoolgrounds. I still remember that girl, she was a little on the chubby side, not quite pretty, she had long dark hair, sort of looked like an Indian, and there was a situation where she was surprised by being told that she was actually a white person, not Indian … That was quite shocking, a machine that projected something like that, and people were moving around in there. I was so interested, and I definitely wanted to see more.”3

Tokyo offered a multitude of ideal diversions for a “science boy,” such as air shows and invention expos, which Honda would sneak off to see all by himself, without his parents’ permission. But more and more, he was drawn to the movie houses. By the third and fourth grade he was reading newspaper critiques and asking friends which movies were worth seeing, and begging his big brothers to take him. “If you had the money, you’d just go to the movie theater and watch whatever,” he said. “It was that kind of time.”

———

Two minutes before noon on Saturday, September 1, 1923, a seismic fault six miles beneath the sea floor off Tokyo unleashed a magnitude 7.9 temblor, mercilessly shaking the Kanto Plain. A forty-foot-high tsunami came ashore and swept away thousands of people, and fires engulfed the city’s wooden structures for days. Nearly 140,000 of Tokyo’s roughly 2.5 million residents were killed and about half the city was destroyed in the Great Kanto Earthquake, Japan’s deadliest natural disaster. Fortunately, the Hondas lived in the low-density western suburbs, where many people survived by escaping to nearby forests and farmland, away from burning debris.

Tokyo’s rapid postearthquake reconstruction created a cosmopolitan, urban environment, where leisure activities now included jazz clubs, modern theater, and cinema. Film was by this time known as daihachi geijutsu (the eighth art), and its form and content had greatly evolved since Thomas Edison’s kinetoscope had arrived in Japan in 1896. The earliest Japanese movies were essentially filmed stage plays that borrowed the conventions of Noh, kabuki, and Shinpa (a style of melodrama popular in the late 1800s) and featured stars of the theater. By the 1920s filmmakers were embracing new narrative styles, and their movies ranged from lowbrow sword-fighting adventures to high-minded studies of the human condition. The quake had leveled all but one of Tokyo’s studios, resulting in a shortage of domestic movies. Films were imported from abroad to fill the void, and Japanese audiences and filmmakers were influenced by Western methods, techniques, and stories.

Thus, the first films Honda saw ranged from ninja shorts starring Japan’s first movie star, Matsunosuke Onoe (nicknamed “Eyeballs Matsu” for his big, demonstrative eyes) to the German expressionist horror masterpiece The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari СКАЧАТЬ