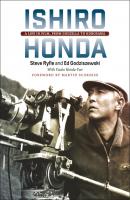

Ishiro Honda. Steve Ryfle

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Ishiro Honda - Steve Ryfle страница 7

Название: Ishiro Honda

Автор: Steve Ryfle

Издательство: Ingram

Жанр: Кинематограф, театр

isbn: 9780819577412

isbn:

The uneasy postwar Japan-US alliance underlies many of Honda’s science fiction films, and while Godzilla and especially Mothra might be interpreted as somewhat anti-American, Honda was increasingly optimistic about the relationship. In his idealized world, America and the “new Switzerland” of Japan are leaders of a broad, United Nations–based coalition reliant on science and technology to protect mankind. Scientists are highly influential, while politicians are ineffective or invisible. The Japan Self-Defense Forces bravely defend the homeland and employ glorified, high-tech hardware; but military operations often fail, and force alone rarely repels the threat. Assistance comes from monsters, a deus ex machina, or human ingenuity. Honda was also frequently concerned with the dehumanizing effects of technology, greed, or totalitarianism.

Honda relied on his cinematographers and art directors to create the look of his films; thus the noirish style of Godzilla, made with a crew borrowed from Mikio Naruse, is completely unlike the larger-than-life look of the sci-fi films shot in color and scope just a few years later by Honda’s longtime cameraman Hajime Koizumi. He was less concerned with visual aesthetics than with theme and entertainment. Therefore, in analyzing Honda’s work, the authors weight these and other story-related criteria, such as tone, characterization, actors’ performances, editing (under the Toho system, editors executed cuts as instructed by the director), pacing, structure, use of soundtrack music, and so on, more heavily than technique or composition. The magnificent special effects of Eiji Tsuburaya are discussed in this same context; detailed information about Tsuburaya’s techniques is available from other sources.17

Honda believed in simplicity of theme. “Yama-san [Kajiro Yamamoto] always used to say … the theme of a story must be something that can be precisely described in three clean sentences,” Honda said. “And it must be a story that has a very clear statement to make. [If] you must go on and on explaining who goes where and does what [it] will not be entertaining. This, for me, is a golden rule.”

———

Research for this project was conducted over a four-year period and included interviews conducted in Japan with Honda’s family and colleagues; archival discovery of documents, including Honda’s annotated scripts and other papers, studio memorandums, Japanese newspaper and magazine clippings dating to the 1950s, and other materials; consultation of numerous Japanese- and English-language publications, including scholarly and trade books on film, history, and culture; consulting previously published and unpublished writings by and interviews with Honda; locating and viewing Honda’s filmography, including the non–science fiction films, the great majority of which are unavailable commercially; and translation of large volumes of Japanese-language materials into English for study.

Only the original, Japanese-language editions of Honda’s films are studied here, as they best represent the director’s intent and achievement. As of this writing, all of Honda’s science fiction films are commercially available in the United States via one or more home video platforms, in Japanese with English-language subtitles, except for Half Human, The Human Vapor, Gorath, King Kong vs. Godzilla, and King Kong Escapes. For these films, the authors viewed official Japanese video releases when possible, and the dialogue was translated for research purposes.18 Honda’s dramatic and documentary films were another matter. To date, only three, Eagle of the Pacific, Farewell Rabaul, and Come Marry Me, have been released on home video in Japan, and no subtitled editions are available. Many others, however, have been broadcast on Japanese cable television over the past decade-plus; and with the assistance of Honda’s family and research associate Shinsuke Nakajima, the authors obtained and viewed Honda’s entire filmography except for two films, the documentary Story of a Co-op, of which there are no known extant elements, and the independent feature Night School; in writing about these two films the authors referred to archival materials and published and unpublished synopses. Yuuko Honda-Yun performed the massive undertaking of translating film dialogue for study. (As this book went to press, it was announced that the rarely seen Night School would be issued on DVD in Japan in 2017.)

Though none of Honda’s non-sci-fi films are currently available in the West, they are analyzed in this volume—admittedly, to an unusual and perhaps unprecedented extent—because they reveal an invaluable and previously impossible picture of the filmmaker and the scope of his abilities and interests, exploring themes and ideas that his genre films often only hint at. And with the advent of streaming media and new channels for distributing foreign films, it seems not unlikely that some of these rare Honda pictures will appear in the West before long.

One pivotal part of Honda’s life that remains mysterious is his period of military service. Honda rarely spoke openly about his experiences, but it is clear that multiple tours of duty and captivity as a POW left psychological scars and informed the antiwar stance of Godzilla and other films. “Without that war experience, I don’t think I would be who I am,” Honda once said. “I would have been so much different had I not experienced it.”19

Honda had collected his war mementos, such as correspondence, diaries, documents, and artifacts, in a trunk that was locked away for the rest of his life. It was his intention to return to this trunk and assemble the material in a memoir, a task never completed. Sources for the account of Honda’s military service in this book were limited to Honda’s writings, interviews with family members, and other secondary materials. The Honda family has decided that the contents of the trunk should remain private. A small number of the trunk’s materials were shown in a 2013 NHK television documentary and subsequently put on limited public display in a museum exhibit. However, the contents have not been archived and made available for research; thus, it is unknown what further details may eventually come to light about Honda’s lost years at war.

———

The book concludes with the first detailed chronicle of Honda’s third career phase, in which he reunited and collaborated with Akira Kurosawa. Beginning with the production of Kagemusha (1980) through Kurosawa’s last film, Madadayo (1993), this period was a rejuvenating denouement for both men, a return to the free spirit of their early days as idealistic Toho upstarts, with Honda rediscovering his love of filmmaking while providing a bedrock of support for “The Emperor,” his oldest and closest friend.

It is a little-known fact that Kurosawa once ranked Godzilla number thirty-four on his list of one hundred favorite films, higher than acclaimed works by Ozu, Ford, Capra, Hawks, Fellini, Truffaut, Bergman, Antonioni, and others. In doing so, Kurosawa wrote: “Honda-san is really an earnest, nice fellow. Imagine … what you would do if a monster like Godzilla emerged. Normally one would forget everything, abandon his duty, and simply flee. Wouldn’t you? But the [authorities] in this movie properly and sincerely lead people [to safety], don’t they? That is typical of Honda-san. I love it. Well, he was my best friend. As you know, I am a pretty obstinate and demanding person. Thus, the fact that I never had problems with him was due to his [good-natured] personality.”20

Honda’s story is about a filmmaker whose quietude harbored visions of war and the wrath of Godzilla, whose achievements were largely unrecognized, and whose thrilling world of monsters was both his cross to bear and his enduring triumph.

“It is my regret that СКАЧАТЬ