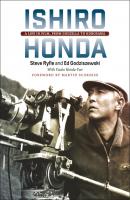

Ishiro Honda. Steve Ryfle

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Ishiro Honda - Steve Ryfle страница 12

Название: Ishiro Honda

Автор: Steve Ryfle

Издательство: Ingram

Жанр: Кинематограф, театр

isbn: 9780819577412

isbn:

The opposite would prove true. Events far beyond his control would doom him to a long military career.

———

Snow blanketed Tokyo on the morning of February 26, 1936. Just before 5:00 a.m., Lt. Yasuhide Kurihara of the First Division overpowered the sleeping policemen guarding the prime minister’s residence. Once inside, Kurihara opened fire—a signal to his comrades outside, who stormed in, guns blazing. A coup was under way, engineered by a rebel faction of young, right-wing army zealots determined to rub out government leaders whose support for the military they considered lacking.

Honda, stationed just a short distance away, was awakened by the shots. Confused, he wondered if the conflict with China had made its way there. Soon the gravity of the situation was apparent: The rebels occupied a square mile of central Tokyo, including the Diet Building. Dubbed the Restoration Army, they railed against the civilian government and invoked Emperor Hirohito to expand Japan’s imperial conquest all the way to Russia. Hirohito, in a rare display of authority, instead denounced them. Soon the 2/26 Incident, as it became known, fizzled; its leaders were soon court-martialed. The rebels had killed a handful on their hit list, but they missed the prime minister and other targets.

In China, late 1930s.Courtesy of Honda Film Inc.

Honda had no knowledge of the plot, but he could easily have been swept up in it. Kurihara, one of the primary instigators, was Honda’s former commanding officer. Sometime before the event, Honda had overheard Kurihara talking to sympathizers about “revolution,” though Honda had no idea what it meant. The night before the coup, Kurihara visited Honda’s barracks, looking for a machine gun. Honda later recalled that Kurihara had hesitated there—perhaps considering whether to recruit these young soldiers for his nefarious mission—before moving on.

Only a small faction within the First Division had participated, but everyone associated with Kurihara was tainted. Their unit was now considered dangerous; the brass wanted them gone. And so in May 1936 Honda and his regiment were sent to Manchukuo under questionable pretenses, on a mission to track down the leader of a Chinese resistance group who, as it turned out, wasn’t in the area.

If not for the 2/26 Incident, Honda would likely have completed his compulsory military service within eighteen months, as was customary. But by the time he came home in March 1937, he had spent two years in the military; and as the war in China escalated, he would be recalled again and again in an apparent series of tacit reprisals against those connected, even tangentially, to the coup.

And yet, even though the revolt had failed and its leaders were duly punished, the violence instilled the fear of further assassinations and terrorist plots. The Diet subsequently increased military spending. The march toward totalitarianism was on.

5

FORGING BONDS

With its progressive acumen, PCL attracted filmmakers more concerned with their craft than with becoming studio power brokers. From 1934 to 1935, several big-name directors left larger, established studios for the young company. Two of these men became dominant figures on the PCL lot: Mikio Naruse, who defected from Shochiku, would develop into one of Japan’s most celebrated directors, a master of sophisticated shomin-geki (working-class drama) films focusing on the plight of women; and Kajiro Yamamoto, from Nikkatsu, was a skilled technician, whose work would achieve tremendous commercial success. Naruse and his staff were considered the artistic group, while Yamamoto’s team was a versatile bunch who developed the type of program pictures that would come to define the studio’s brand. Yamamoto had a paternal attitude toward his devoted corps of assistants, a commitment to pass on the craft to the next generation. Bespectacled, handsome, and perpetually well dressed, Yama-san, as he was fondly called, became Honda’s greatest teacher.

Born in Tokyo in 1902, Yamamoto was unimpressed with early, theater-influenced Japanese cinema, but he was inspired by pioneering director Norimasa Kaeriyama’s work, including The Glow of Life (Sei no kagayaki, 1919), considered revolutionary for its lack of stage conventions and its use of actresses over female impersonators. In 1920 Yamamoto dropped his economics studies at Keio University and joined Nikkatsu’s Kyoto studios. For the next few years he wrote screenplays, worked as an assistant director, and acted under the pseudonym Ensuke Hirato. He began directing films in 1924.

Yamamoto had caught Iwao Mori’s attention as a member of the old Nikkatsu Friday Party, and Mori lured him over to PCL in 1934 to direct the first of many films starring Kenichi “Enoken” Enomoto, known as Japan’s “king of comedy.” Yamamoto was naturally curious and enjoyed genre hopping; he made musicals, melodramas, and later crime thrillers and salaryman comedies. At the height of World War II he would direct several big-budget, nationalist war propaganda films that were highly successful at the box office. His career would last well into the 1960s.

Honda became one of Yama-san’s most trusted disciples. From Yama-san, Honda learned all aspects of the craft with an emphasis on writing, as Yamamoto stressed that directors must write screenplays. While shooting, Yamamoto often scribbled in a journal, a practice that Honda adopted.

Honda also learned from Yamamoto how to treat his staff. Yama-san would throw parties at his home for cast and crew as a way of creating a family atmosphere; when Honda became a director, he would do the same for his charges. Yamamoto had a soft, quiet demeanor and always treated his protégés in equal terms. He called them by name: It was always Honda-san or the more familiar Honda-kun, never “hey you” or the condescending language other directors often used. He never sent them to buy cigarettes or do menial errands. Years later, Honda would show the same respect to his own crew members.

“He didn’t want yes-men around him,” Honda recalled. “We always went drinking with him, though. But he was never an autocrat … Since [Yamamoto] was so knowledgeable, his stories were always interesting. He was also frank on the set and would ask me to write parts of the script. And then he would use it.”1

Honda described Yamamoto as a connoisseur. “He was more like a free spirit. He was not like us, he was not all about movies. Movies were only a part of his life. He liked other things too, such as music. So I learned a lot of things from him.”2

———

Honda’s two-year absence had stalled his career, while his peers advanced. His first job upon returning to work was on Yamamoto’s two-part drama A Husband’s Chastity (Otto no teiso, 1937). Senkichi Taniguchi, Honda’s friend since the Friday Party days, was now Yamamoto’s chief assistant director (or first assistant director), while Honda remained a second assistant director. Still, Honda accepted his situation and held no resentment toward the studio or his rank-and-file cohorts.

Released in April 1937, A Husband’s Chastity marked several milestones. It was a big hit, the first PCL film to turn a profit. It did so despite the refusal of Shochiku, Nikkatsu, and other studios to exhibit PCL movies in their theaters, a retaliation against PCL’s practice of hiring away its competitors’ actors and directors. For Honda, the film had another significance: it marked his meeting with an intensely ambitious new recruit, a man who would become his lifelong best friend.

The job of assistant director in the Japanese studios was not unlike that in Hollywood: keeping the production schedule, preparing call sheets, maintaining order on the set, and so on. Unlike their American counterparts, however, the Japanese СКАЧАТЬ