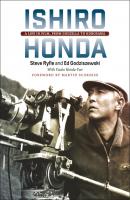

Ishiro Honda. Steve Ryfle

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Ishiro Honda - Steve Ryfle страница 3

Название: Ishiro Honda

Автор: Steve Ryfle

Издательство: Ingram

Жанр: Кинематограф, театр

isbn: 9780819577412

isbn:

• Friends, family, and colleagues, including Takako Honda, Naoto Kurose (Honda Film Inc.), Bruce Goldstein, Dennis Bartok, Michael Friend, Chris Desjardins, Jeffrey Mantor, David Shepard, Raymond Yun, Hinata Honda-Yun, Sergei Hasenecz, Norman England, Oki Miyano, Jenise Treuting, Gary Teetzel, Erik Homenick, Glenn Erickson, Richard Pusateri, Keith Aiken, Bob Johnson, Nicholas Driscoll, Stephen Bowie, Bill Shaffer, Stig Bjorkman, Edward Holland and Monster Attack Team, Akemi Tosto, Joal Ryan, and Stefano Kim Ryan-Ryfle.

INTRODUCTION

[Japanese] critics have frequently dismissed Honda as unworthy of serious consideration, regarding him merely as the director of entertainment films aimed at children. By contrast, they have elevated Kurosawa to the status of national treasure. As for the men themselves, by all accounts Honda and Kurosawa had nothing but respect for one another’s work. Prospective studies of the history of Japanese cinema should therefore treat Honda’s direction of monster movies and Kurosawa’s interpretation of prestigious sources such as Shakespeare as equally deserving of serious discussion.

— Inuhiko Yomota, film historian

In August 1951, as Japan’s film industry was emerging from a crippling period of war, labor unrest, and censorship by an occupying foreign power, the press welcomed the arrival of a promising new filmmaker named Ishiro Honda. He was of average height at about five-foot-six but appeared taller to others, with an upright posture and a serious, disciplined demeanor acquired during nearly a decade of soldiering in the second Sino-Japanese War. There was something a bit formal about the way he spoke, never using slang or the Japanese equivalent of contractions—he wasn’t a big talker for that matter, and was usually immersed quietly in thought—yet he was gentle and soft-spoken, warm and likeable. A late bloomer, Honda was already age forty; and if not for his long military service, he likely would have become a director much earlier. He had apprenticed at Toho Studios under Kajiro Yamamoto, one of Japan’s most commercially successful and respected directors; and he hinted at, as an uncredited Nagoya Times reporter put it, the “passionate literary style” and “intense perseverance” that characterized Yamamoto’s two most famous protégés, Akira Kurosawa and Senkichi Taniguchi, who were also Honda’s closest friends.

“Although their personalities may be similar, their work is fundamentally different,” the reporter wrote. “Ishiro Honda [is] a man who possesses something very soft and sweet, yet … his voice is heavy and serene, giving off a feeling of melancholy that … does not necessarily suit his face. The many years he lost out at war were surely a factor…. The deep emotions must be unshakeable.”

Honda’s inclinations, it was noted, were more realistic than artistic. He didn’t share the “Fauvism” of Kurosawa’s painterly compositions.1 He took a dim view of the flashy, stylistic film technique that some of his contemporaries, including Kurosawa and famed director Sadao Yamanaka, with whom Honda had also apprenticed, borrowed from American and European cinema of the 1920s and 1930s.

“I do not want to deceive by using superficial flair,” Honda said. “Technique is an oblique problem. The most important thing is to [honestly] depict people.” A beat later, he was more introspective: “This may not really be about technique. Maybe it is just my personality. Even if I try to depict something real, will I succeed?”

The newspaper gave Honda’s debut film, The Blue Pearl, an A rating, declaring it “acutely magnificent.” And with a bit of journalistic flourish, the paper contemplated the future of the fledgling director, admiring his desire to “practice rather than preach, [to] cultivate the fundamentals of a writer’s spirit rather than being preoccupied with technique, a fascination with the straight line without any curves or bends…. How will this shining beauty, like a young bamboo, plant his roots and survive in the film industry?”2

———

A tormented scientist chooses to die alongside Godzilla at the bottom of Tokyo Bay, thus ensuring a doomsday device is never used for war. An astronaut and his crew bravely sacrifice themselves in the hope of saving Earth from a wayward star hurtling toward it. Castaways on a mysterious, fogged-in island are driven mad by greed, jealousy, and hunger for a fungus that turns them into grotesque, walking mushrooms. A pair of tiny twin fairies, their island despoiled by nuclear testing, sing a beautiful requiem beckoning the god-monster Mothra to save mankind. Invaders from drought-ridden Planet X dispatch Godzilla, Rodan, and three-headed King Ghidorah to conquer Earth, but an alien woman follows her heart and foils their plan. A lonely, bullied schoolboy dreams of a friendship with Godzilla’s son, who helps the child conquer his fears.

The cinema of Ishiro Honda brings to life a world of tragedy and fantasy. It is a world besieged by giant monsters, yet one in which those same monsters ultimately become Earth’s guardians. A world in which scientific advancement and space exploration reveal infinite possibilities, even while unleashing forces that threaten mankind’s very survival. A world defined by the horrific reality of mass destruction visited upon Japan in World War II, yet stirring the imaginations of adults and children around the world for generations.

Honda’s Godzilla first appeared more than sixty years ago, setting Tokyo afire in what is now well understood to be a symbolic reenactment of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It was a major hit, ranking eighth at the Japanese box office in a year that also produced such masterpieces as Seven Samurai, Musashi Miyamoto, Sansho the Bailiff, and Twenty-Four Eyes. It was subsequently sold for distribution in the United States, netting sizeable returns for Toho Studios and especially for the American profiteers who gave it the exploitable new title, Godzilla, King of the Monsters! If the triumph of Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon—which took the grand prize at the 1951 Venice International Film Festival, and subsequently received an honorary Academy Award—had brought postwar Japanese cinema to the West, then it was Honda’s monster movie that introduced Japanese popular culture worldwide.

Only fifteen years after Pearl Harbor, Godzilla, King of the Monsters! (famously reedited with new footage starring Raymond Burr, yet featuring a predominantly Japanese cast) surmounted cultural barriers and planted the seed of a global franchise. It was the forerunner of a westward Japanese migration that would eventually include everything from anime and manga to Transformers, Power Rangers, Tamagotchi, and Pokémon. Godzilla became the first postwar foreign film, albeit in an altered form, to be widely released to mainstream commercial cinemas across the United States. In 2009 Huffington Post’s Jason Notte declared it “the most important foreign film in American history,” noting that it had “offered many Americans their first look at a culture other than their own.”3

An invasion of Japanese monsters and aliens followed in Godzilla’s footsteps. With Rodan, The Mysterians, Mothra, Ghidorah the Three-Headed Monster, and many others, Honda and special-effects artist Eiji Tsuburaya created the kaiju eiga (literally, “monster movie”), a science fiction subgenre that was uniquely Japanese yet universally appealing.

Honda’s movies were more widely distributed internationally than those of any other Japanese director prior to the animator Hayao Miyazaki. During the 1950s and 1960s, the golden age of foreign cinema, films by Kurosawa, Mizoguchi, and other acclaimed masters were limited to American art house cinemas and college campuses, while Honda’s were emblazoned across marquees in big cities and small towns—from Texas drive-ins to California movie palaces to suburban Boston neighborhood theaters—and were also released widely in Europe, Latin America, Asia, and other territories. Eventually these films reached their largest overseas audience through a medium they weren’t intended for: the small screen. Roughly from the 1960s through the 1980s, Godzilla and company were mainstays in television syndication, appearing regularly on stations across North America. Since then, they have found new generations of viewers via home video, streaming media, and СКАЧАТЬ