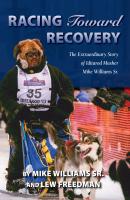

Racing Toward Recovery. Lew Freedman

Чтение книги онлайн.

Читать онлайн книгу Racing Toward Recovery - Lew Freedman страница 7

Название: Racing Toward Recovery

Автор: Lew Freedman

Издательство: Ingram

Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары

isbn: 9781941821671

isbn:

We couldn’t move very well and we were grimacing and frowning. All of the coaches looked at us and they were smiling, then they were snickering and then they were laughing. We made the adjustments quickly.

At that time my body was built very differently than it is built now. I was about five-foot-seven inches tall and weighed around 150 pounds. I was also a pretty fast runner, so because of my speed they made me a running back. I was a sprinter back then. Mostly I played positions for a smaller, fast guy. I was a running back throughout my football career and I also returned punts and kickoffs. On defense I was a linebacker. Everybody played offense and defense both at the time. I loved playing football. I really loved it. Our team was the Chemawa Braves.

I was 150 pounds when I first went out for football, but I grew. I got to be 160 pounds and then 170 pounds. I am big-boned, so I had the body frame to handle more weight. I was a fast runner, but I also had some strength from the lifestyle I led in the outdoors at home in Akiak, hunting and fishing and chopping wood.

We didn’t have a lot of size on our team. I think our linemen averaged like 180 or 190 pounds. We played a lot against white schools that had guys that were six-foot-two hulks who weighed 250 pounds. I think our tallest guy was six-foot-one. We were smaller, but we were fast. Our teams weren’t bad.

Our team had a wonderful coach. His name is Kugie Louis. He was the football coach and the track coach. I got the best coaching. He built our stamina and toughness. He was always big on fundamentals. He stressed knowing the fundamentals of the game and always being prepared to play. He talked about us being prepared to run and being prepared to have your body withstand pain. He was the best coach I ever had.

In high school I played football, basketball, and competed on the track team. I was the captain of the freshman team in basketball in ninth grade. As a sophomore I played on the junior varsity and the varsity. My junior year I was cocaptain of the basketball team.

As a member of the track team I ran the 100-yard dash and the 220. I also did some low hurdles and high hurdles. My best event was probably the 100-yard dash. My best time was 10.5 seconds. My best 220 time was under 23 seconds. I wasn’t slow.

The Chemawa school was a lot like being at Wrangell in that I was living away from home again and a lot of the program was aimed at acculturation. They still wanted to strip away our culture, I think, but it was a little bit more liberal in that we were allowed traditional dances. The Navajos did some Indian dancing and the Northwest tribes did their dances. They were good dancers, too.

They did tell us that our goal should be to go to college. Academics were stressed and I think they had a pretty good academic program. I was a pretty good student overall. I had good enough grades to make it to the honor roll. I was a good athlete who was good in sports and that’s how the other students knew me. I had not participated in student council or student government in any way, but at the end of my junior year I decided to run for student body president. I won.

That was the first time I had ever been involved in student government and I didn’t know what I was getting into. Suddenly, I was into politics and I got interested in that. From there I dropped sports and focused on student government. During the summer after my junior year I went to a training program in the central part of Missouri at Westmont College to learn more about it.

I was given the opportunity to spend three weeks at this small, liberal arts college not far from St. Louis. There were kids there from all over the United States. It was an intensive program where I learned how to conduct meetings and understand Roberts Rules of Order, politics, and the issues of student governments. It was designed to help develop leadership and that’s where I think I got all of the leadership skills I needed to carry out my presidential duties my senior year.

So I gave up sports for politics for my senior year. I could have done both, but I decided to focus more on academics and student government.

I think my four years in Oregon really helped shape me as a person. I broadened my horizons. I got a chance to play on sports teams. I became president of the student body and learned about political issues. That was a whole new area for me then. The school did ask quite a bit from its students. I got an exposure to the western way of life in the United States, and by that I mean western as in American as opposed to Native. But Chemawa also made us learn practical skills. We did our own banking and by that I mean that we started a student bank my senior year. We started other programs. One was like a junior entrepreneurship and we started a business selling hamburgers. The business was for fund-raising for the student body.

We started another program built around alcohol education. We had all heard for years from white people and from movies that there was an image of “the drunken Indian” out there in society. We started a program when I was school president to try and focus on changing that image of the drunken Indian. It was basically a counseling program for people with substance abuse problems, both for students and staff who needed help. I was only twenty years old at the time, but I recognized that my people had problems with alcohol that needed to be fixed.

One thing we worked on was alcohol awareness in terms of the harm it could do. I worked with a guy named Steve Labuff. We also started a campus patrol program to help people who were drunk and to prevent crime problems. We wanted our campus to be safe and to make sure people got home all right.

Part of the idea was also to improve the image of Alaska Natives and Indians by promoting heroes. Ira Hayes was one of the six Marines that worked to raise the flag on Iwo Jima during World War II in the famous photograph. He helped to raise that flag.

My father saw the future pretty well. Although he was very involved in preserving Native traditions he also knew that things were going to change. He told his children that we should get a good education and get as much schooling as we could. I think getting that western education was important. I remember my dad saying, “I think you guys need to go get your education and try your best in school because you’re going to be dealing, negotiating for land. You’re going to be negotiating your rights. You’re going to be negotiating a lot of big issues that are going to come up.”

He really knew what he was talking about on this subject. He said we should try to go to the best schools that have the best education and provide the best opportunities. “Try to get as much education as you can so you can protect what we have,” he said. “We’re going to be challenged for our way of life.” His generation did not get a similar education and many could not read or write, nor could they understand these government policies that were popping up.

He was right. The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act was implemented in 1971. The act was signed into law by President Richard Nixon and formalized land dispersal in Alaska to twelve Native corporations and 200 village corporations. A few years later the Alaska Pipeline opened and began pumping oil from the North Slope of Alaska not far from Barrow. Congress passed the Endangered Species Act in 1973 and that affected Alaska Natives’ hunting and fishing prospects. The Molly Hootch Case resulted in a consent decree in 1976. That came from a lawsuit filed by Alaska teenagers that provided for more education in villages. New high schools were built all over. If that had become the policy a decade earlier I never would have had to go live in Wrangell or go to school in Oregon.

All of these huge issues affected rural Alaskans economically, in our subsistence lifestyle, and in the way we educated our children.

When I was a teenager going to Chemawa my father—and other Elders—said getting a white man’s education was important, regardless of whether we liked it СКАЧАТЬ